Bringing a little mechanical buddy back to life.

This article has an accompanying four-part video series in the Patreon feed. Sign up at the Noble Patron level to see them!

A good friend of mine recently bought a house built in 1924. It has many beautiful period details, including the original mortise lock set in the front door. A mortise lock set is a one-piece mechanism that includes one or more locks and latches all in one unit. It’s called a “mortise lock” because to install it you have to cut a huge mortise (square cavity) in the end of the door. This is not the easiest thing to do, and it requires your door to made of a quality solid hardwood. The combination of installation difficulty and doors being made of other materials likely led to the downfall of these mechanisms. They are marvels of engineering, however, and were absolutely built to last. This one has been in continuous use for nearly 100 years, and though it wasn’t working well anymore, it’s surprising how little was actually wrong with it. This effort wasn’t just an idle curiosity. The broken original door hardware had prompted previous owners to install a modern deadbolt and a criminally hideous security gate over the original door. By restoring this lock set we will be doing a great service to the neighborhood.

The original is a full featured lock set, including a door latch with multiple modes, and a deadbolt. There are also automatic coordination features in the deadbolt, as we’ll see. These are the sorts of tricks you can do with a one-piece lock and latch set that modern deadbolts have forgone in the name of inexpensive installation.

The first step is to get the lock set out of the door. Let’s see what we’re facing here.

It was so well sealed in there that it took a fair amount of quality time with razor blades and knives to free it from the paint. In principle, once liberated, it slides right out of the door.

Before we can do that, however, the handles must be removed. In this sense, mortise locks are very much like modern hardware- the handles are holding everything in, and are last-on-first-off.

Behind the door hardware, we see the original stain and/or preservative is intact as well, which is nice. This may be creosote or linseed-oil-based. Furniture from this period would have likely used shellac, but something structural like a door would not have such a labor-intensive process in a middle-class home.

With the handles removed, we can turn our attention to the lock set itself.

The lock did then slide out of the door, although there was a lot of resistance, for reasons we’ll see shortly. Patrons can see video of the removal in the Patreon feeds, along with lots more details on this repair.

The first step is to take the cover off. We know there are at least three problems we’re trying to solve- the door did not latch, the deadbolt handle spun freely with no effect, and the latch mode buttons on the front appeared to have no effect.

That creative repair was part of what held the case together and something went “sproing” inside when I removed it. That’s always unsettling, but let’s get inside and see what’s what.

Mostly, everything was really really dirty. Like, really filthy. It’s almost like nobody has taken it apart and cleaned it for 100 years. There was a nice spider nest in one corner, but even that was abandoned. She was all, “the rent was cheap, but it’s filthy! I’m outta here as soon as these 258 kids are born”.

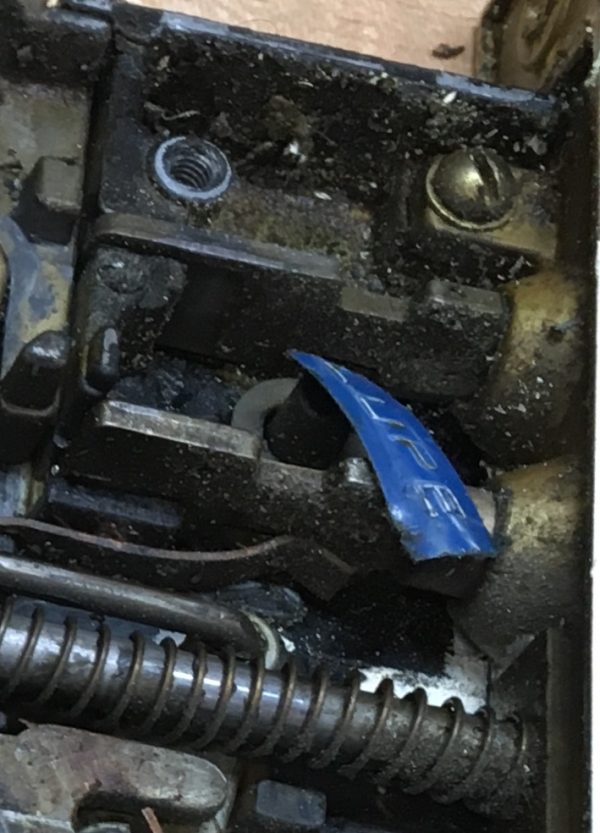

You never know what you’ll find inside old machinery, and this was a really notable example of that. If I was up against a wall with a gun to my head, I could not tell you how a name tag from a 1970s-era embossing label maker got inside this sealed lock set.

Anyhoo, now that we’re in like Quinn (hi Scott), we can see what’s going on and what might need fixing.

The first question is the mode buttons on the front edge. In one position, these allow you to open the door with the handle from other side, as normal. In the other position, only the inner door handle can work the latch. It’s kind of a “soft lock”. It’s roughly equivalent to the handle lock on a modern bathroom door, except that you can lock yourself out quite irrevocably with this. No key or pick will let you back in if the door swings closed behind you. It’s a neat feature though, and a nice little extra layer of security. The mode buttons seemed to have no effect on this device, however.

In this case, it seemed that things were just seized up. Cleaning and lubrication should sort it out. There’s nothing physically broken or out of place here.

The next problem to look at is that the normal door latch didn’t catch when the door was closed. The plunger didn’t spring back outward after being pushed in.

There’s a complex linkage connecting the latch and the deadbolt that is really interesting. It’s a feature whereby when you turn the key to unlock the deadbolt, if you turn a little further, it also pulls the main latch backwards. This allows you to unlock and open the door in one motion. The deadbolt also has a linkage that disables the door latch when extended, so it’s actually a double-lock of sorts. These locks are really clever, and delightfully well-engineered.

The final question was the deadbolt, wherein the handle spun freely with no effect. This was definitely going to be something broken.

Okay, so this all seems fixable. Let’s get this thing taken apart and cleaned up.

Cleaning and lubrication should solve most of the issues, but not all. We have three parts that need more invasive attention. First is that broken deadbolt handle. I decided to make an extension for the rod and braze it on. You can weld wrought iron (it welds very well, in fact), but it’s a small part and I don’t trust my skills to do that. Brazing should be plenty strong, however.

Okay, let’s repair and extend that shaft. To the machine shop!

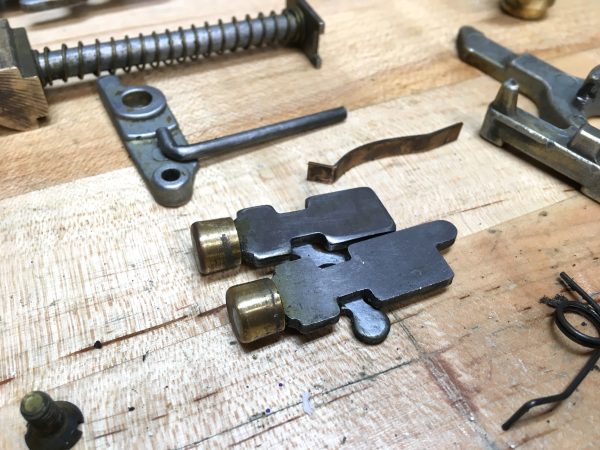

The next thing to address is the bolt that a previous repairperson had made to (presumably) replace a factory pin. In addition to being one of the screws holding the case together, it was also anchoring one of the springs that forms the latch mechanism. As I said before, the repair was a clunky ground-down machine screw that stuck out way too far and interfered with installation of the lock. I grabbed some brass off the junk pile and made a replacement. Patreon Patrons can see video of the making of this screw, so sign up now if you’d like to be one of them. They had drilled out the boss on the enclosure that holds this bolt, and I can’t change that, so I made the new bolt to the same dimensions, but in the style of the original hardware.

The final thing to address is the latching door handle. While cleaning and lubrication fixed the internal mechanism, the handle itself was sloppy and didn’t feel right. A quick inspection of the parts revealed why. The handle has a shaft that threads into it, and the handle clamps to said shaft with a pair of setscrews. The other end is square, and slides into the latch mechanism. However, this shaft was so worn out that it was hard to tell what shape it was even supposed to be. The setscrews were barely holding the handle in place, and the fit was very sloppy. The threads on the inside of the handle were also quite trashed.

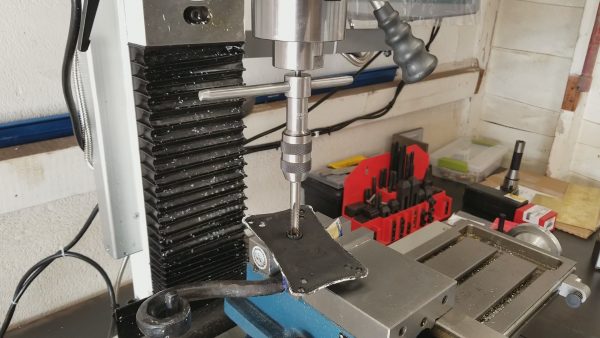

Since I was going to have to make a new shaft anyway, I decided to cut new threads in the handle. I opted to match the pitch of the old ones (there was enough left there to measure), but choose a larger diameter. The tap should find the old threads and simply enlarge them. The old threads were 18-per-inch (measured with a thread gauge), which is still a common standard. Conveniently, the dimensions of the worn hole were the tapping size for a ⅜” thread, so I opened up the threads to ⅜-18. Doing this straight was a tricky job, because the entire handle is a hand-wrought pile of curves. There’s nary a straight line or flat surface on the entire structure anywhere.

Next I needed to remake the shaft. Since the original was so trashed, I couldn’t really tell what it was supposed to look like. However the way it worked was easy enough to deduce, so I made a new part that did the same job and mated to the other parts I had. Things are a bit worn inside the lock, so mine would be a better fit anyway.

I have video of the making of this shaft as well. To see it, head on over to the Patreon Patrons feed, or sign up now to get access.

You’ll note the grooves on the shaft. These are for the setscrews on the handle. The original had four grooves, but I made only two. Four grooves, in my opinion, only serve to weaken the threads on the shaft. In theory four grooves provide four different orientations for the handle, but you can get that same effect by adjusting how the shaft inserts into the lock mechanism. Either way you get four possible handle positions, so two grooves are sufficient. I suspect the original was made this way for cheaper manufacturing. It’s clearly cut from bar stock that has the groove already in it on all four sides, rather than being bespoke-machined from scratch as my replacement is.

The final step was to clean every part thoroughly, then lubricate and reassemble the whole lock. I took photos during disassembly so I could remember how it all went, but truth be told you could probably figure it out. There’s only one way it all goes back together, it just saves time not to have to reverse engineer it from scratch at reassembly time.

For lubrication, not being a locksmith, I did some research on the tuberwebs. The general recommendation seems to be dry graphite lubricant for a lock like this, because it won’t evaporate (like many liquid lubricants would), won’t drip off the parts (like oil would), and won’t get gummed up with crud over time (like grease would). The other nice thing about dry graphite lube is that you can get it in an aerosol, suspended in alcohol. As needed, you can inject it into the lock through any available crack after the lock is reinstalled. The alcohol flashes off and you’re left with a dry layer of graphite on things. I gave everything a good coating during assembly which should last a good long while. The sad part of this approach is it makes everything black, after I just spent time making it all look nice inside.

For a look at lubrication and reassembly, check out the associated Patreon video for this post. Yes, that’s four videos to go along with this blog post. That’s how much I heart you, Patrons.

Assembly is the reverse of removal. The lock set is slid into the mortise and secured with the large screws at top and bottom. Then the deadbolt cylinder is threaded into the front. There are two very long set screws that go into the end plate of the device to secure the lock cylinder and prevent it from being unscrewed from the outside. Then the door handles and deadbolt handle can be reinstalled on the two sides of the door.

With everything back together, I’m pleased to say every feature on the door now works perfectly, and should be good for another hundred years. This was a mechanical restoration, not a cosmetic one, so there’s a little more work to do around removing sloppy old paint from the wrought iron, replacing some of the screws, and so on. For a look at the final result and a demo of all the features of this old lock, you’ll want to check out the Patreon videos.

After completing the project, I received this update from the happy customer: “Door hardware functioning within normal parameters.”. That’s the highest compliment an engineer can receive.

Excellent restoration, and a great write up.

I enjoyed reading that.

I installed four reclaimed age appropriate 1870s pitch pine internal doors in my house, replacing the modern fire doors that were there. Each door had an original lockset but no keys. I was able to remove, open, clean, and make new keys to fit each door. The doors are never locked, though, but nice to know they can be.

That’s great! I love stuff like this- it was built to last, and to be repaired, often with basic tools (because frankly, they were made with basic tools).

😀

😉

“We’re in like Quinn” – I would adopt this phrase if I thought I knew anyone else who would appreciate it. It would make a nice T-shirt design along with that picture of all the knolled dismantled lock parts

Hah, that’s a great idea! I may just do that!

“That creative repair was part of what held the case together and something went “sproing” inside when I removed it. That’s always unsettling, but let’s get inside and see what’s what.”

That made me laugh out loud, because that exact same thing happened to me when I opened up a mortise lock to fix it.

Hehehe, indeed, the dreaded “sproing”

“That creative repair was part of what held the case together and something went “sproing” inside when I removed it. That’s always unsettling, but let’s get inside and see what’s what.”

That made me laugh out loud, because that exact same thing happened to me when I opened up a mortise lock to fix it.

I grew up in a house with these all over the place. Even the interior doors had them, but with locking mechanisms which took skeleton keys. The major problem we had was all of the encrusted layers of paint which got slapped on haphazardly. Excellent work!

Thanks very much! 😀